public squares in focus

Klariza Juntilla / ARTH3701 with Prof. Gul Kale

Public squares are the urban thoroughfares that connect a city's past, present, and future as well as its social life, culture, and politics.

As such, a successful public square ensures the accessibility and the participation of all living within a city.

This photo journal aims to discuss two public squares in Istanbul: the historic Sultanahmet Square, also known as the Hippodrome of Constantinople and the modern Taksim Square.

These two squares will be cross-analyzed with significant events in Turkish history, particularly the Ottoman and Byzantine eras in Istanbul and the following periods of modernization and shifting political regimes in the country.

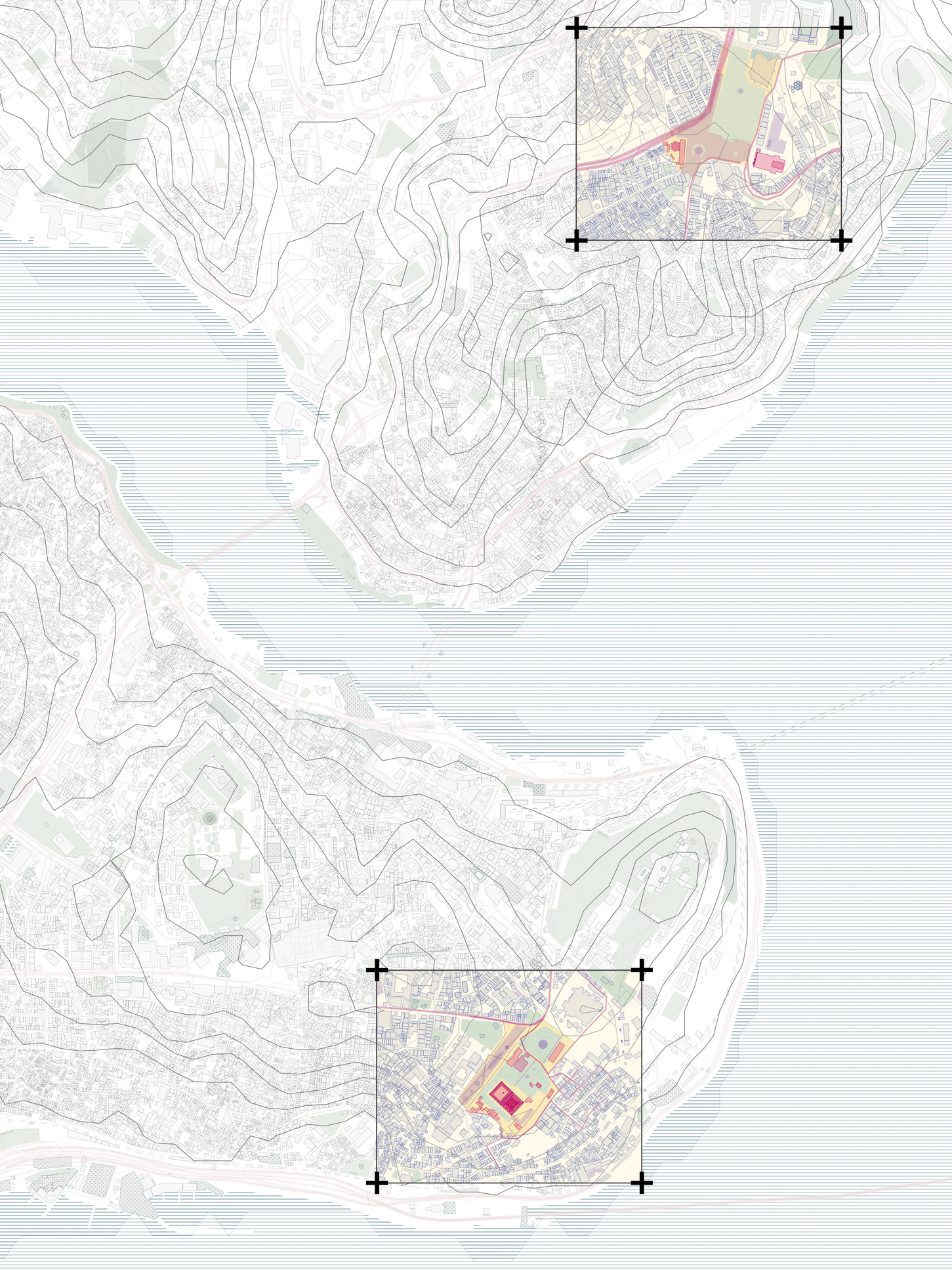

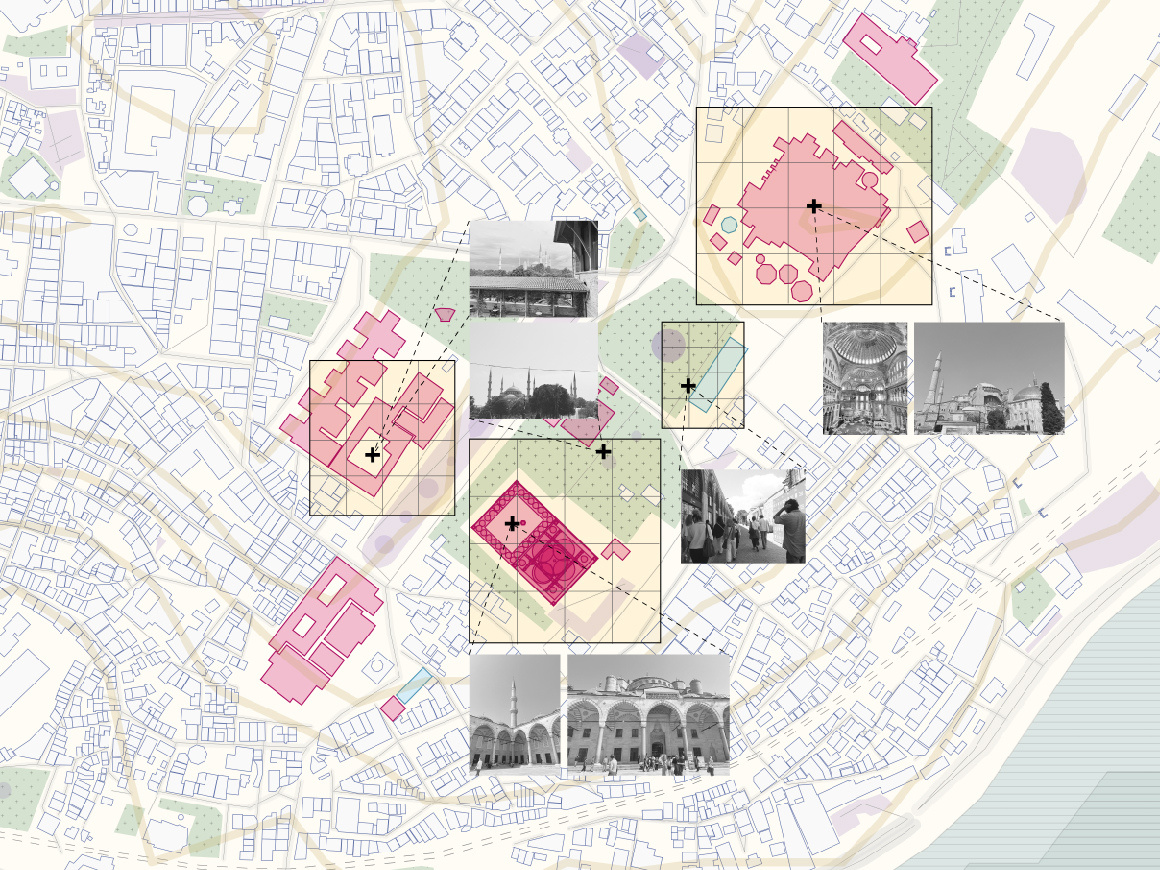

The Hippodrome of Constantinople is found in the Fatih district of Istanbul, located strategically along the coast of the Marmara Sea. During the Byzantium period, it was a public arena primarily used for chariot races and it was the center for social life for citizens. The Hippodrome is now known as Sultanahmet Square, which houses many important landmarks of the city.

The placement of these monuments within a public space is a deliberate decision by the Empire, serving as symbols to its authority and strength.

The decision to build on a hill near the water was also a strategic decision, as monuments and landmarks are visible from the sea, further amplifying and demarcating the Empire’s power.

Architecture can be used as a political tool to display power, establish national identities and selectively retell a nation’s history to fit a desired narrative.

This notion has specific implications on Istanbul, with it being a historical city that has undergone multiple transformations under various governmental powers.

Photographic print on albumen paper (1870)

Typical urban spaces such as public squares have a unique place in Istanbul’s landscape given the city’s morphology. The language of the city is displayed in the layers of urban fabric from different eras directly interacting with one another, where the opposite can also be true, in areas of the city where selective features were conserved while others were destroyed. The way in which certain architectural sites are restored or conserved can be indicative of the desires of differing periods of political power.

Istanbul’s historical background has influenced its unique city planning and its applications began in the 1850s during the Ottoman Empire. This design process closely reflected the city planning efforts in Europe, which occurred in response to issues caused by industrialization. However, in the Ottoman Empire, the transformation of a traditional city did not occur by means of master planning, but by partial developments.

Ara Güler

Ara Güler

Following the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the founding of the Turkish Republic, the new government worked to define and affirm a new identity as a nation-state. Modernizing Turkey's largest cities was a crucial step to achieve this goal. Agricultural communities also began to migrate to urban areas in search of employment at this time due to industrialization.

To successfully integrate new groups into the metropolis, there was a need for large scale investment by the government in housing and infrastructure.

Ara Güler's Istanbul: 40 Years of Photographs

The modernization process during this time and the desire to form a new national identity results in the destruction of important historic sites and the conservation of sites that align with governmental ideals.

Ara Güler's Istanbul: 40 Years of Photographs

The modernization process during this time and the desire to form a new national identity results in the destruction of important historic sites and the conservation of sites that align with governmental ideals.

THE MODERN ERA

Henri Prost, a French architect and urbanist, played a pivotal role in Istanbul’s urban planning. In 1936, he was commissioned by Mustafa Kemal Mustafa Kemal Atatürk of the newly formed Republic of Turkey to design an urban plan for the city. It is important to note that although Prost was not as radical as Haussmann in his plan for Paris, he includes the demolition of several Ottoman sites in his proposal. His sensibilities as an urbanist along with the intentions of the governing body are reflected in here.

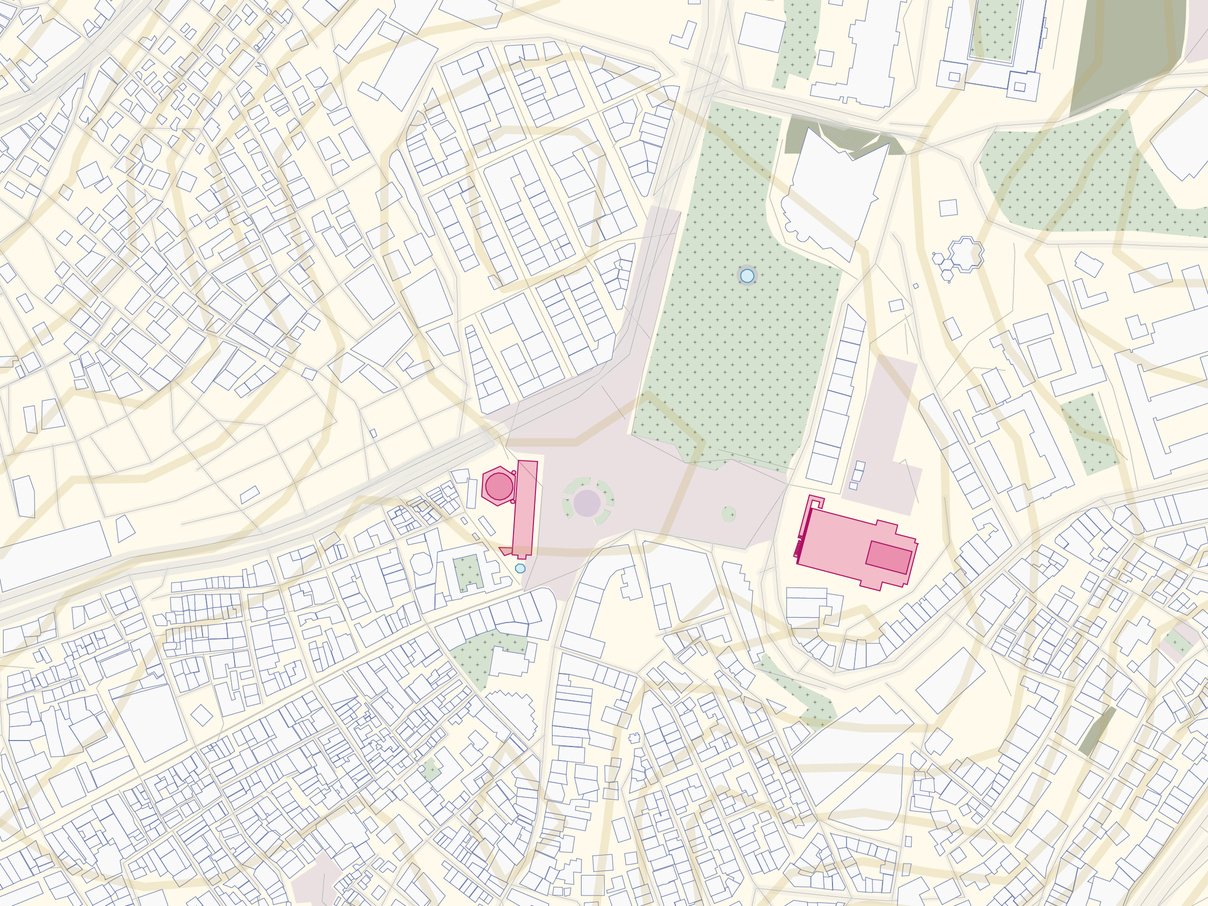

That being said, Prost is a preservationist when it relates to physical structures as he wants to preserve the city’s rich archaeological history. However, when it comes to the Ottoman urban fabric he is an interventionist, which is supported by the government’s desire to distance themselves from their Ottoman past. For example, in his master plan for Taksim Square, Prost proposed to demolish the former site of the 19th century Taksim Artillery Barracks for the new public plaza and Gezi Park.

taksim square

In his essay in the collection City Squares by Catie Marron, George Packer writes that in newer countries, one can find two types of public squares. One that is older, more chaotic and populated and one that is newer, planned, orderly and deserted.

While Sultanahmet Square can be an example of the former, Henry Prost’s Taksim Square is an example of the latter. Taksim Square represents the idealized desires of a nation, a space that imposes its desires on the inhabitants and does not allow for much informal setting or occupation.

This is evident in the landmarks located in Taksim Square, especially when compared to those in Sultanahmet Square. The “spolium” found in Sultanahmet Square are used to symbolize the power and yield of the Empire. In Taksim Square, buildings and monuments are used more to establish a new national identity.

The Republic Monument, inaugurated in 1928, celebrates the 5th anniversary of the foundation of the Republic of Turkey and can be found at the center of Taksim Square. Notably, the square is also bordered by Gezi Park, which from 1560 to 1939 was the site of the Pangalti Armenian Cemetery, a significant cemetery which was considered the largest non-Muslim cemetery in Istanbul’s history.

Erasure and destruction to establish a common narrative is not uncommon at Taksim Square, as there is a strong desire for the government to establish itself as a new nation.

In 1952, Taksim Mosque was proposed on the south-western side of the site and was another highly politicized landmark. The government halted construction in 1980 due to a military coup and when democracy was restored with the 1983 Turkish general election, it was determined that the project was not of public interest.

With every change of administration, there is a persistent divide between the public and the government over the construction of Taksim Mosque. It is not until 2017 when it is authorized for construction.

With the history of all of these monuments and landmarks in mind, it is clear that Taksim Square is a highly politicized space that is associated with republicanism and secularism.

In 2013, Gezi Park was the site of protests against plans to redevelop the space and replace it with housing developments and a shopping center. The construction of the Taksim Mosque was also amongst the pleas by protesters.

The prospect of the destruction of Gezi Park brought forth the issues of secularism, freedom of assembly and expression to the forefront. The fact that this protest took place at Taksim Square, a space created with the intention to define a national identity, perfectly exemplifies the relationship between spaces and people.

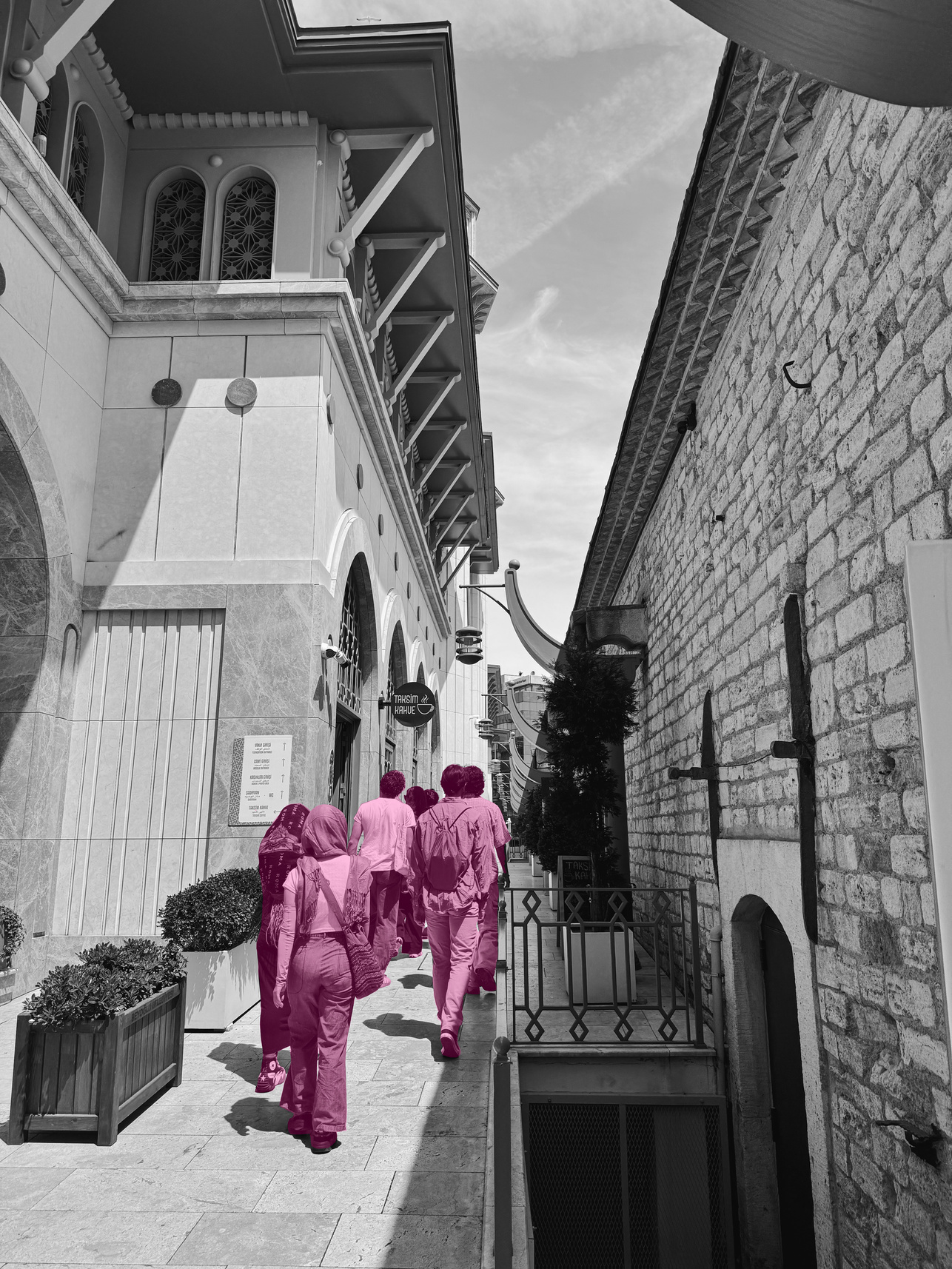

As much as the architect or the urban planner wants to control the lived experience of an individual, the reality of any given space is the exact opposite.

People that occupy a space define it; the inverse is a fallacy.

This is why it is important to examine the evolution of the public square in Istanbul. At its most basic purpose, public squares are meant to provide an open setting in which people can gather, somewhere private bodies and common citizens can interact with one another on a public scale.

It follows that regardless of how you decide to analyze or materialize a public square, it is purely defined by the people that pass through it and thus its accessibility and usability is extremely important. The identity of a public square relies on the people that occupy it.

By nature, urban design and architecture can be expressed in both formal and informal ways. The fluidity of this expression allows for agency over one’s existence and experience through a city. The public squares discussed in this journal are essentially a government ordained and commissioned public space. It is ironic, how much agency over space can people have in a place created for them by the people who rule over them?

The physical space of a public square is not worth much if it does not allow for interaction by the people that occupy it.

Adjaye, David. “Djemaa el-Fnaa, Marrakech: Engaging with Complexity and

Diversity.” Essay. In City Squares: Eighteen Writers on the Spirit and

Significance of Squares Around the World, edited by Catie Marron. Harper

Collins, 2016.

Anzilotti, Eillie. “What Public Squares Mean for Cities.” Bloomberg, May 9, 2016. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-05-09/in-the-essay- collection-city-squares-18-writers-discuss-the-role-of-public-spaces.

Bakirtzis, Charalambos. “Secular and Military Buildings.” In The Oxford

Handbook of Byzantine Studies, edited by Robin Cormack, John F. Haldon,

and Elizabeth Jeffreys, 373-374. (2008; online edn, Oxford Academic, 21

Nov. 2012).

Bilsel, Fatma Cânâ. 2004. “Shaping a Modern City Out of an Ancient Capital

Henri Prost’s Plan for the Historical Peninsula of Istanbul.” In . Barcelona,

SPAIN: 11th Conference of the International Planning History Society

(2004). http://www.etsav.upc.es/personals/iphs2004/eng/en-pap.htm.

Göksoy, Ekin Can. “Remembrance of Places Past: The Pangalti Armenian

Cemetery.” Essay. In Negotiation of Differences in the Shared Urban

Space, edited by Alina Poghosyan and Vahram Danielyan, 47–65. Yerevan:

American University of Armenia, 2017.

Gül, Murat. Architecture and the Turkish City: An Urban History of Istanbul

since the Ottomans. London: I. B. Tauris & Company, Limited, 2017.

Mango, Cyril A. Byzantine architecture. London: Faber/Electa, 1986.

Packer, George. Introduction to Part 3 History: Influence on Humanity,

Introduction. In City Squares: Eighteen Writers on the Spirit and

Significance of Squares Around the World, edited by Catie Marron. Harper

Collins, 2016.

Shafak, Elif. “Taksim Square, Istanbul: Byzantine, Then and Now.” Essay. In City

Squares: Eighteen Writers on the Spirit and Significance of Squares

Around the World, edited by Catie Marron. Harper Collins, 2016.

Tekeli, İlhan. “The Story of Istanbul’s Modernisation.” Architectural Design 80,

no. 1 (January 2010): 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.1007.

Türeli, İpek. (2010). Ara Güler’s Photography of ‘Old Istanbul’ and Cosmopolitan

Nostalgia. History of Photography, 34(3), 300–313.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03087290903361373

Türeli, Ipek, and Meltem Al. “Walking in the Periphery: Activist Art and Urban

Resistance to Neoliberalism in Istanbul.” Review of Middle East Studies 52,

no. 2 (2018): 310–33. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26562585.

biblio.